The body has two external surfaces – the skin and several mucosal surfaces such as the mouth, lining of the gut, nasal passages, airways, urinary tract and genitals, notably the vagina in women. Of these the mouth, oesophagus (gullet) and vagina are relatively frequently infected by fungi. Only one fungus is exquisitely adapted to cause infection at these three sites: Candida albicans.

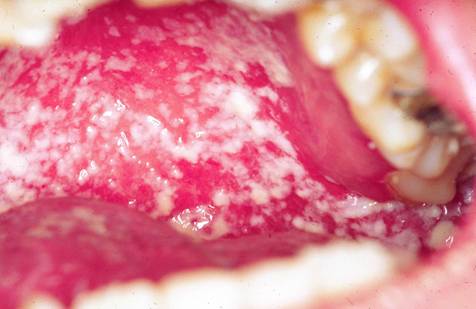

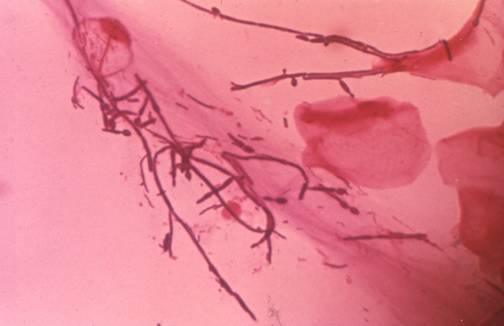

Thrush is the general term used for mucosal infection by Candida in the mouth and vagina. Candida grows on the surface of the mucosa, with minimal penetration, beyond the surface layer of cells. In some people there is virtually no inflammatory response and there is a lot of Candida, leading to white ‘plaques’ on the surface of the mucosa (pseudomembranous) or considerable vaginal discharge. In other people, there is marked inflammatory response leading to a reddened (erythematous) mucosa and considerable irritation and discomfort. In the mouth dentures may be coated with Candida which causes a local inflammatory reaction, called denture stomatitis.

Thrush is often recurrent because Candida albicans is a commensal organism, mostly living in harmony with humans in the gut and on mucosal surfaces in very low numbers. Only when that balance is disrupted does thrush occur.

Videos

From our blog

Factsheets

Oral thrush

| NAMES Oral thrush, oropharyngeal candidiasis, oral candidiasis/candidosis/Candida |

| DISEASE A painful mouth with loss of taste is the most common symptom. The commonest pattern is the pseudomembranous form, but an exanthematous type is also found. Occasionally, denture-related candidosis or angular cheilitis (corner of the mouth) are the primary manifestations. In AIDS, the pseudomembranous form predominates. |

| FUNGI Candida albicans (>98%). Rarely C. glabrata or Candida krusei. |

| GLOBAL BURDEN Oral thrush in HIV/AIDS occurs in ~2.5 million people worldwide based on ~90% of patients not taking but needing anti-retroviral therapy. At least another 1 million are affected who do not have HIV infection. |

| RISK FACTORS Very common in HIV/AIDS, with declining immunity, and with leukaemia/HSCT unless prevented with antifungals. Common in newborns or patients on head/neck radiotherapy. Occasional in asthmatics taking inhaled steroids and other immunocompromised patients. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (rare genetic disorder) caused by either AIRE or STAT1 mutations, in most cases. |

| DIAGNOSIS Inspection of the mouth (including under dentures) showing white plaques or erythematous patches. Fungal culture and/or microscopy |

| TREATMENT Topical: nystatin, amphotericin B, clotrimazole, chlorhexidine, others Oral: fluconazole, itraconazole solution, ketoconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole Rinse mouth out immediately after using steroid inhalers for asthma. CURRENT GUIDELINES |

| OUTLOOK Usually excellent. May be associated with oesophageal candidiasis, which does not resolve with topical therapy. May recur, especially in AIDS, denture wearers and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis patients. Antifungal resistance a problem if recurrent treatments. |

Pseudomembranous oral candidiasis with plaques on the buccal mucosa

Severe thrush of tongue in a patient with AIDS

Angular cheilitis caused by Candida albicans

Fungal hyphae invading the epithelium in a patient with oral thrush

Oesophageal candidiasis

| NAMES Oesophageal candidiasis, Candida oesophagitis |

| DISEASE Oesophageal candidiasis usually co-exists with oropharyngeal disease, although in 30% of cases, no oral lesions are visible. Sore throat on swallowing, or difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), nausea and vomiting are the commonest symptoms. |

| FUNGI Candida albicans (rarely Candida glabrata) |

| GLOBAL BURDEN Candida oesophagitis affects an estimated ~1.4 million people as ~20% of HIV/AIDS patients not on anti-retroviral therapy, and ~0.5% if on antiretroviral therapy develop it. Other patients might increase the numbers by 10-20%. |

| RISK FACTORS HIV infection and AIDS when the CD4 count is below 100 x 106/l, and is itself an AIDS-defining condition. Cancer and neutropaenia. Rare reports of oesophageal candidosis in immunocompetent individuals after omeprazole therapy, suggesting that hypochlorhydria favours colonisation. |

| DIAGNOSIS Endoscopy showing white plaques on the surface of the oesophagus is the only definitive means of making the diagnosis with microscopy, culture and biopsy (often negative) confirming Candida involvement. Barium swallow is insensitive, but distinctive if abnormal. |

| TREATMENT Fluconazole 200 mg daily. Alternatives include IV amphotericin B, anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin, or oral solutions of itraconazole and posaconazole. Topical therapy is ineffective and ketoconazole is inferior. CURRENT GUIDELINES |

| OUTLOOK Response rates over 90%, but relapse common in AIDS. Rare complication of perforation and stricture. |

Moderately severe oesophageal candidiasis in a non-HIV infected woman

Vulvovaginal thrush

| Name(s) | NAMES Vaginal thrush, vulvovaginal candidiasis/candidosis, chronic VVC (cVVC), recurrent VVC (rVVC) |

| Disease | DISEASE As the name indicates, vulvovaginal candidiasis can involve both the vagina and the vulva. More common symptoms are burning, itching, soreness and vaginal creamy discharge. Vulval examination shows erythema of the labia minora, majora, perineum often with oedema and fissuring. Sometimes perianal skin is affected. Examination of the vagina reveals erythema and/or adherent white/creamy discharge Vulvovaginal candidosis (VVC) is mostly uncomplicated but it is regarded as complicated when there are severe symptoms, recurrent episodes, during pregnancy, or colonisation with non-albicans Candida species or in immunocompromised patients. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis (rVVC) is defined as more than four confirmed episodes over 12 months. It affects some 5-9% of healthy women during their childbearing years, or those on hormone replacement therapy. Another group of women get cVVC, a recently recognised entity. |

| Fungi | FUNGI Candida albicans (can be Candida glabrata following azole use, rarely other Candida species), |

| Global burden | GLOBAL BURDEN Thrush is common. About 70% of all premenopausal women develop thrush at some point in their lives. By a mean age of 24 years, 60% of women had suffered at least one episode of vulvovaginal candidosis; 36% had at least one episode a year; 3% had it ‘almost all the time’. Estimates suggest 135 million (8%) women get 4 or more attacks of vulvovaginal candidosis annually across the world. In these patients there is often a worse response to initial treatment and a shorter time to relapse. There are no estimates of the frequency of cVVC, but is less common than rVVC. |

| Risk factors | RISK FACTORS Certain conditions increase the incidence and possibly the severity of vulvovaginal candidosis, including pregnancy, antibiotic use, diabetes mellitus and cystic fibrosis. HIV-seropositive women are not more likely to develop vaginal candidiasis than controls. Oestrogen status is important, accounting for post-menopausal women having rVVC on HRT. Other risk factors such as corticosteroid use and frequent antibiotic use should be identified. If sporadic risk factors can be identified prophylactic antifungal treatment can be used at the time. In many cases, however, the risk factors are persistent or cannot be identified. |

| Diagnosis | DIAGNOSIS The vaginal pH is normal (3.8-4.5) in VVC, in contrast to bacterial vaginosis when it is >4.5. Microbiological testing is important and almost always positive in acute episodes. Microscopy and culture of vaginal or vulval sample showing Candida. Some cultures may be positive in the absence of symptoms. A small number of patients with acute episodes have negative cultures. – RECURRENT VVC is diagnosed when there are at least 4 episodes in 12 months. Often these are diagnosed presumptively by responsiveness to antifungal treatment. Cultures and microscopy may be negative, but it is important to exclude other causes of vulva discomfort and discharge. – CHRONIC VVC diagnostic criteria have recently been formulated (Hong et al, 2014). Highly distinctive features present for at least 3 months are: previous or current positive culture (or microscopy), exacerbation with antibiotics, discharge and marked improvement during menstruation. Other features commonly found, but not quite as specific include pain on intercourse, vulval soreness and vulval swelling. Discharge and itching are not distinctive features of cVVC. Most patients have a positive culture, but not all. They improve with antifungal therapy. – The most common differential diagnosis is bacterial vaginosis (BV) and patients may flip between VVC and BV. Other differential diagnoses include contact dermatitis to something applied intra-vaginally (Powell, 2010), desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, foreign body (usually a tampon), and others. |

| Treatment | TREATMENT TOPICAL: almost all are azoles such as clotrimazole. Azole drugs are not effective for C. glabrata and so this can be treated with nystatin pessaries, available in some countries. Fluconazole should not be used in pregnancy as there is increased risk of cardiac defects in babies, a risk probably not associated with itraconazole. The management of uncomplicated acute VVC consists of either topical or oral therapies, usually as a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg, or 2 doses of 100 mg itraconazole. In treatment-naïve patients all topical and oral azole therapies give an 80-95% clinical and mycological cure rate in non-pregnant women. Patients should be advised to avoid local irritants e.g. soaps, perfumed products and tight fitting synthetic clothing. Recurrent and cVVC respond to longer courses of daily treatment for 3- 6 months. For C. glabrata and resistant cases, topical applications of boric acid gelatin capsule 600 mg daily, inserted into the vagina, for 14 days, OR flucytosine cream 5 g /day for 14 days (Sobel at al, 2003) or a mixture of flucytosine (1 g) and amphotericin B (100 mg) formulated in lubricating jelly base in a total 8 g delivered dose (White et al, 2001). Flucytosine cream is effective but is not widely available. Rare instances of fluconazole resistance are seen in Candida albicans. CURRENT GUIDELINES |

| Outlook | OUTLOOK Most cases of thrush respond well to therapy and the interval between episodes is long. Recurrence may follow antibiotic use and sex. Recurrent use of azole antifungal agents can lead to colonisation with azole-resistant Candida. There are few alternative therapeutic agents available, namely nystatin and boric acid. The latter has been shown to have excellent efficacy but can only be prescribed by specialists from hospital pharmacies. When rVVC responds poorly to given treatment other causes for the symptoms need to be excluded and the patient referred. Patients with rVVC must be followed-up regularly and samples for fungal culture, identification and susceptibility testing taken every 3-4 months. |

VVC

Candida balanitis

Note: If you are a patient who has (or might have) thrush of the penis, please refer to the NHS website for more information.

| NAMES Candida balanitis |

| DISEASE Patients complain of soreness or irritation of the glans penis, and less commonly, they have subpreputial discharge. |

| FUNGI Candida spp., particularly C. albicans. Malassezia spp. and dermatophytic fungi are rare causes of penile infections. Several bacteria (Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Pseudomonas spp., Gardnerella vaginalis, Treponema pallidum, Chlamydia trachomatis, anaerobes and Mycoplasma spp.) can also cause balanitis. |

| GLOBAL BURDEN Common. C. albicans balanitis is the most frequent infection of the penis (~35%). In different patient populations the prevalence of balanitis has been reported to vary from 0% in uncircumcised Danish boys to 11-12.5% in uncircumcised men seen in urology clinics. It has been estimated that globally, balanitis occurs in up to 3-4% of uncircumcised males. |

| RISK FACTORS |

| DIAGNOSIS |

| TREATMENT CURRENT GUIDELINES |

| OUTLOOK |