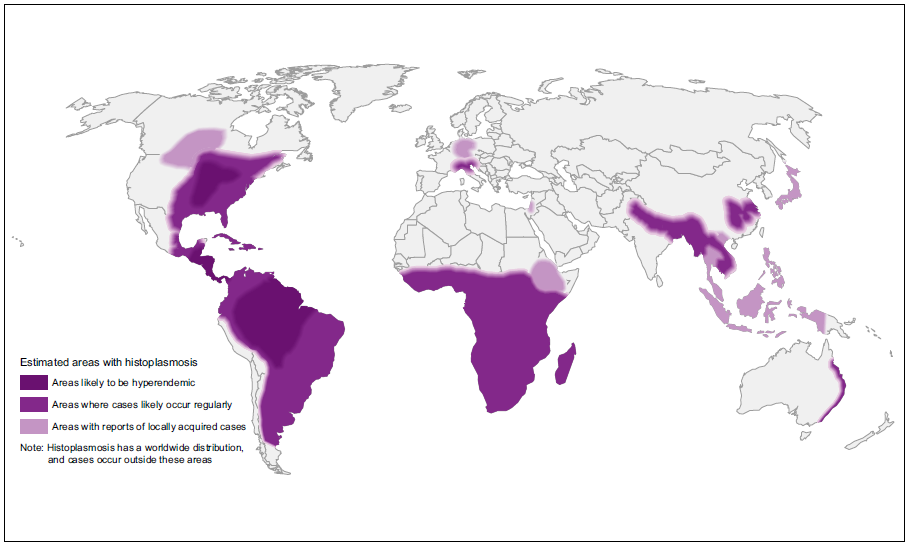

Endemic mycoses are caused by dimorphic fungi (Coccidioidomyces, Paracoccidioidomyces, Blastomyces, Histoplasma) that live as moulds in the environment but grow as yeast cells inside the human body. Many are geographically limited – especially paracoccidioidomycosis and coccidioidomycosis, others have a nearly global distribution, notably histoplasmosis. These diseases are seen in normal people who are exposed and in immunocompromised individuals.

In some areas, endemic mycoses account for up to 30% of community-acquired penumonias but may initially be mistaken for bacterial pneumonia, delaying antifungal treatment (Azar et al, 2020).

Many dimorphic fungi are endemic to certain parts of North America but increasing numbers of cases are being seen outside these regions because of increased travel and climate change (Ashraf et al, 2020).

For a review of endemic mycoses in immunocompromised patients please see Malcolm & Chin-Hong (2016).

Clinical lectures

Coccidiodomycosis (Valley Fever) research & advocacy

The Valley Fever Center of Excellence is based in Arizona USA and provides educational resources for the public as well as healthcare providers.

There is a designated study centre based in the USA. You can find out about the work of the Coccidioidomycosis Study Group here.

Read patient stories

Factsheets

| NAMES Coccidioidomycosis, San Joaquin Valley fever, valley fever |

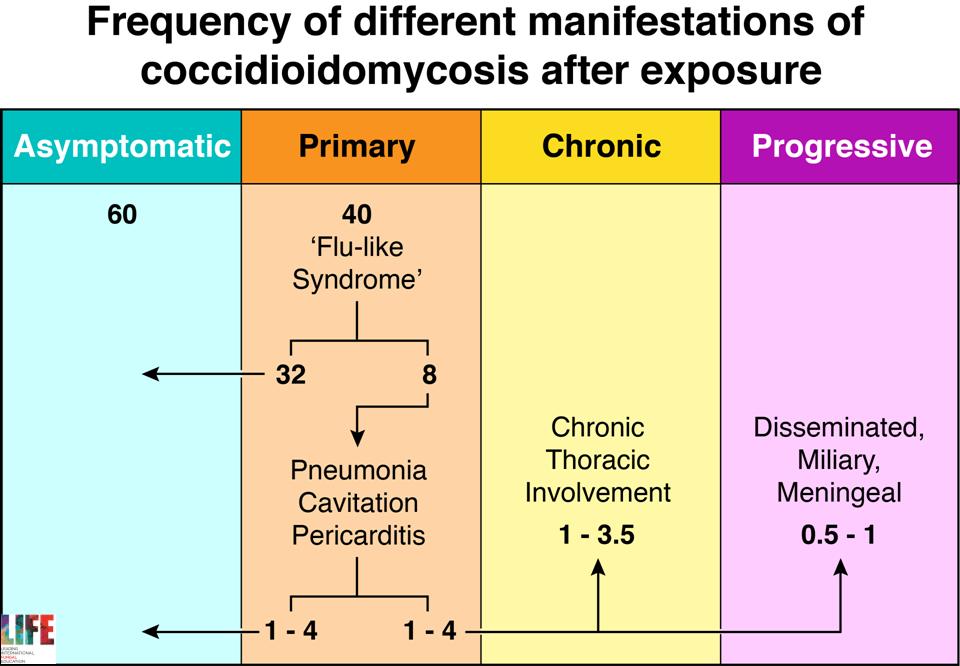

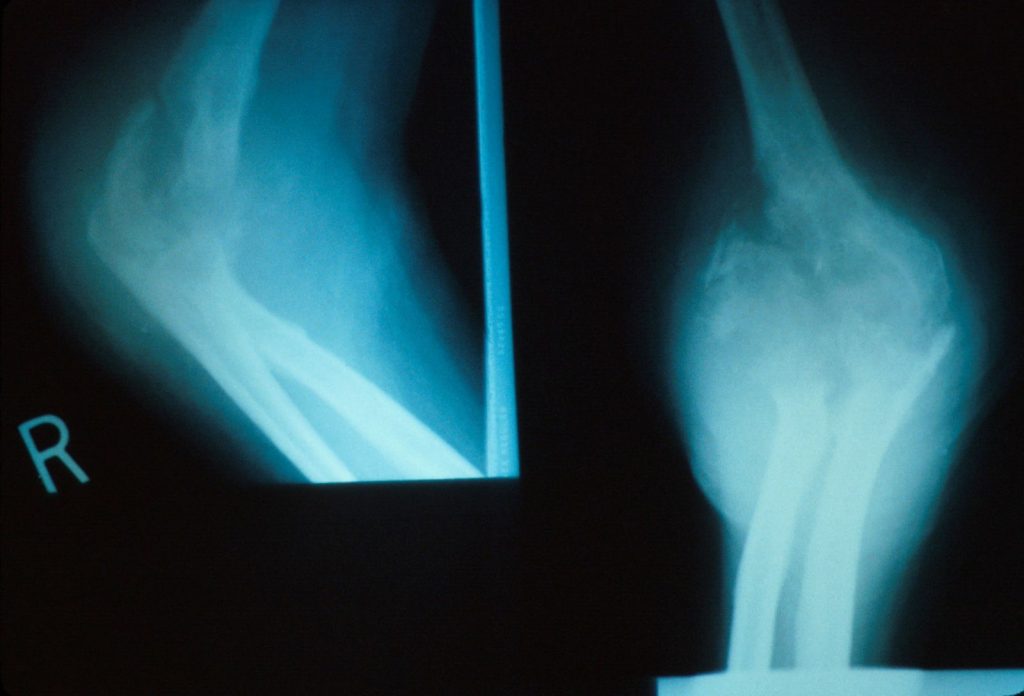

| DISEASE Initial infection results in symptoms in 40% of individuals, which are self-limited in 80% of these people. Typical features are a short-lived ‘flu-like’ syndrome (fever, cough and pleurisy), sometimes associated with erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme (especially in women). In those whose disease is not self-limited, most progressive disease involves the lungs. A progressive pneumonia (primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis) may occur with continuing fever, pulmonary symptoms and eosinophilia. This may also resolve spontaneously, and varies in severity. In immunocompromised individuals and rarely in previously well individuals, a milary, reticulonodular type of pulmonary disease that is characteristic of early disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Following a primary infection pulmonary nodules or cavitation may occur, which may or may not progress. Patients with nodules are usually asymptomatic. Upper lobe cavitation may resemble chronic pulmonary aspergillosis or tuberculosis. Patients develop chronic productive cough, haemoptysis, weight loss and chest pains. Dissemination, which is usually clinically silent, may occur to any body site, the more common locations being the skin, meninges, bones or joints, lymph nodes and other soft tissues. The clinical presentation may be delayed weeks or months after the primary infection. Localised swelling, sometimes with a discharging sinus, is common for many sites. Bone infection may present with a pathological fracture. Joint infection is typically a monoarthritis. Coccidioidal meningitis presents sub-acutely, similarly to tuberculous meningitis, with headache, lethargy and declining mental status. |

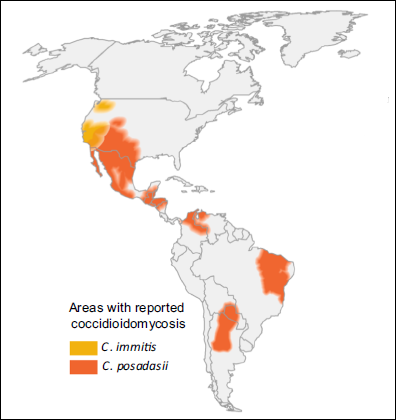

| FUNGI Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii (no difference in disease or diagnostic performance between species) |

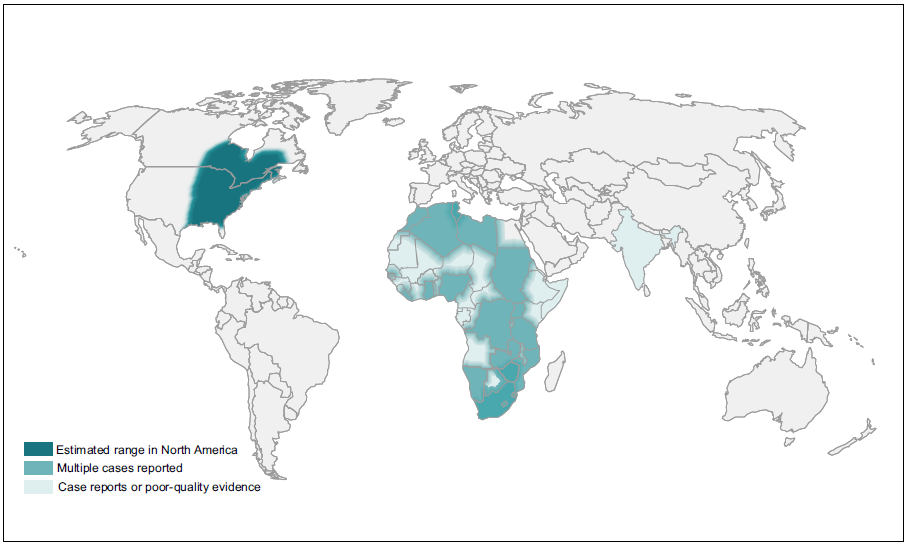

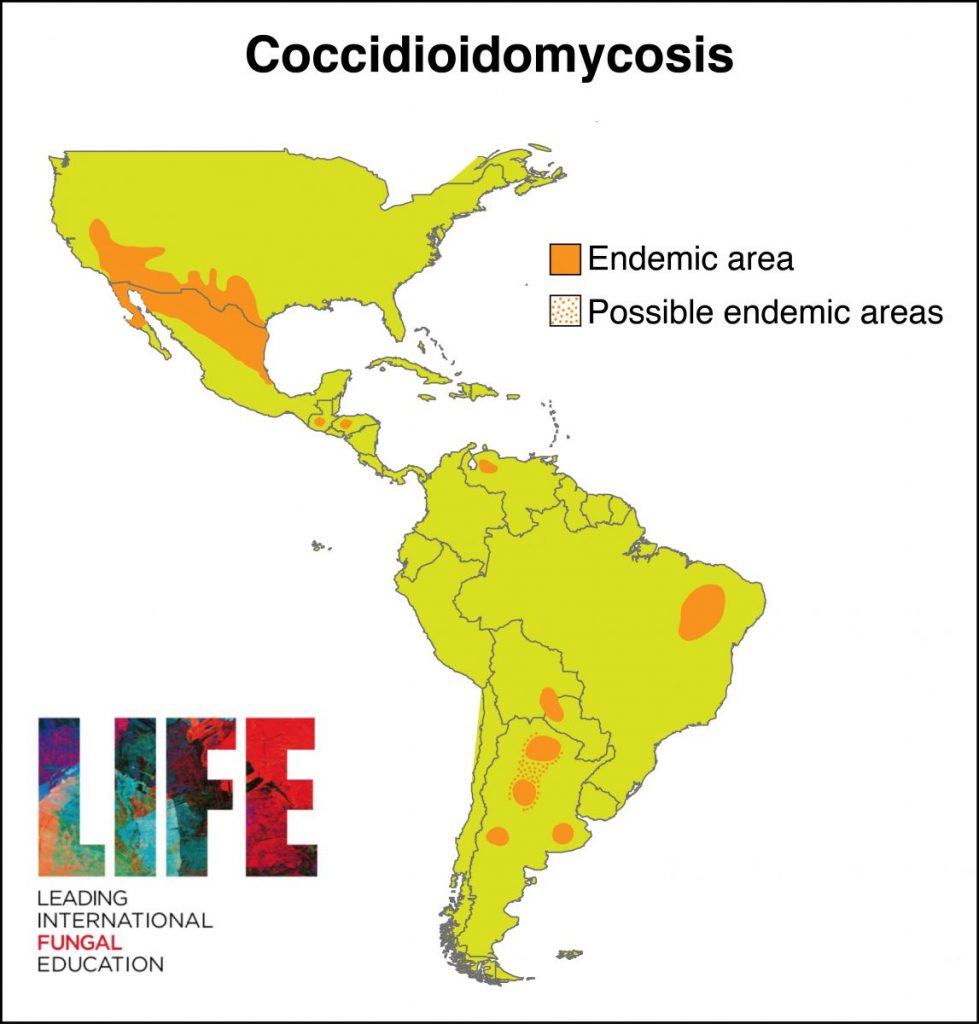

| GLOBAL BURDEN Coccidioidomycosis is restricted to the Americas (see map below). An estimated 150,000 infections occur annually in the USA, and an unknown number in central and South America. Approximately 25,000 new, clinical cases of coccidioidomycosis are reported annually in the USA leading to ~75 deaths per year. Occasional epidemics occur. Case numbers have been rising in Arizona, possibly related to immigration to the state and building on previously wild desert areas, with 7 cases/100,000 persons in 1990, increasing to ~75 cases/100,000 persons in 2007. The most affected countries outside the USA are Mexico, Guatemala, Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina. |

| RISK FACTORS Most patients with coccidioidomycosis are previously healthy. Dissemination is more common in certain racial groups including Filipinos and African-Americans, as well as men. Pregnancy (second or third trimester) increases the risk of dissemination. Immunocompromised patients, especially those on corticosteroids or with advanced HIV infection or AIDS, are at particular risk of dissemination. Patients who do not produce interleukin 12 and/or gamma interferon are more likely to develop disseminated coccidioidomycosis, as are those with a STAT3 genetic defect (Hyper IgE syndrome or Job’s syndrome). |

| DIAGNOSIS As C. immitis is never a commensal organism or a laboratory contaminant, isolation of the organism in culture is diagnostic. C. immitis is a Biosafety level 3 pathogen and must be managed accordingly. C. immitis grows on many fungal media, but poorly, or not at all, on standard bacterial media such as blood agar. C. immitis is difficult to culture from blood and CSF, even in the context of disseminated disease or meningitis. The highly characteristic appearance of spherules in direct microscopy or histological sections confirms infection. Serology with IgG or IgM antibody detection is sensitive and usually signifies infection, if detectable. Falling titres is indicative of an improvement. In meningitis, the CSF usually has features similar to those of TB: elevated protein, reduced glucose, and many lymphocytes visible. The key diagnostic test is detection of anti-coccidioidal antibodies in CSF. 1,3-β-D-glucan is detectable in CSF and in endemic areas is likely to distinguish coccidioidal meningitis from tuberculous meningitis and cryptococcal meningitis, especially if cryptococcal antigen is negative. In nodular or chronic cavitary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, the radiology is not usually distinctive and a history of travel or residence in an endemic area important to considering the diagnosis. |

| TREATMENT Pulmonary nodules do not usually require treatment, as long as they remain stable and patients are asymptomatic. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are currently the preferred agents, usually in doses of 400 mg daily. Posaconazole is also very active. Fluconazole is preferred for meningitis. Itraconazole is preferred for bone and joint infection. For coccidioidal meningitis, either high dose (800 mg/d) fluconazole or intrathecal amphotericin B. CURRENT GUIDELINES |

| OUTLOOK Coccidioidal meningitis needs to be treated lifelong, as it is incurable. Complications including communicating hydrocephalus. The relapse rate for chronic cavitary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis after 12 months of azole treatment is about 50%. Other forms of coccidioidomycosis are usually curable if treatment is given over several months, with relapse rates of 10-30%. – Read about attempts to develop a vaccines at ASBMB Today |

Natural history of primary infection with Coccidioides immitis

Cutaneous coccidioidomycosis in a 17 year old Caucasian living in the Bay Area

Lymph node localization of coccidioidomycosis in a Mexican immigrant to the USA

Destruction of the elbow with a pathological fracture all related to longstanding bone and joint coccidioidomycosis

Bone scan showing disseminated coccidioidomycosis to multiple sites

Right upper lobe cavity with an air-fluid level (courtesy of Neil Ampel)

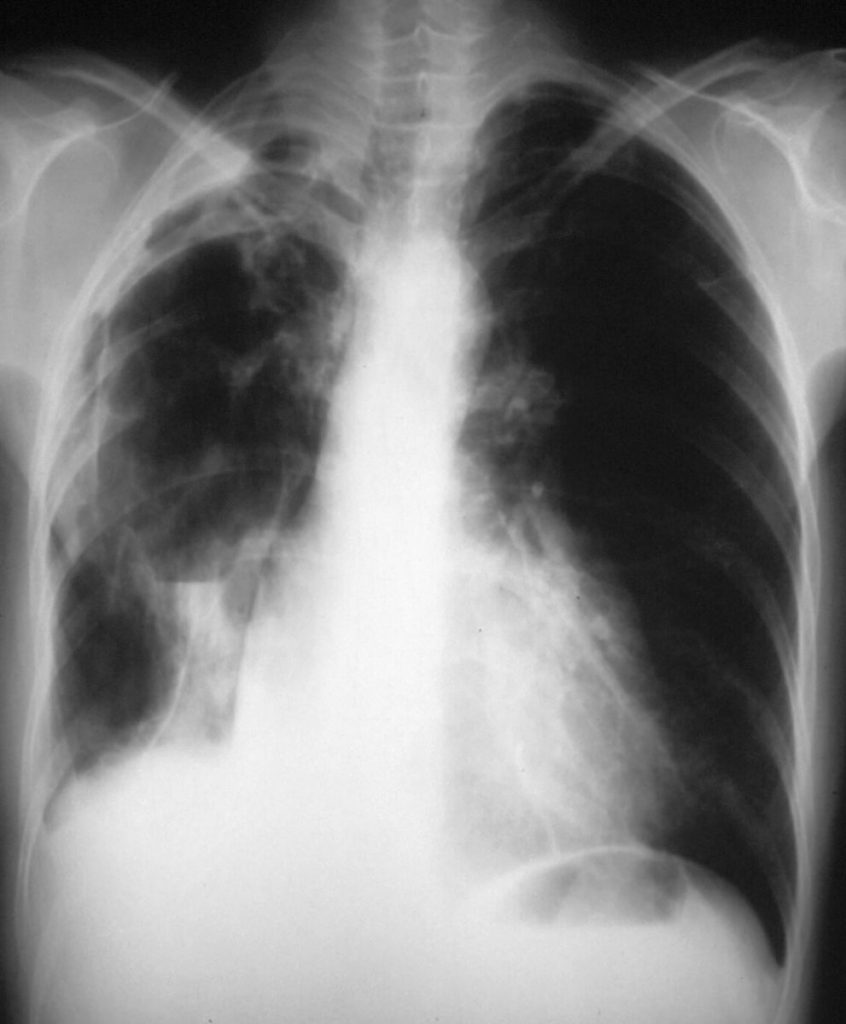

Primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis in California, with ongoing fever, night sweats, cough and weight loss after 4 weeks, and increasing right lower lobe shadowing

Small pulmonary cavity in the right upper lobe in pulmonary coccidioidomycosis

Severe chronic cavitary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis of the right lung, showing one very large pulmonary cavity, with some pleual thickening and smaller cavities in the right apex

Right upper lobe nodule (courtesy of Neil Ampel)

For further radiology information and images please see Jude et al (2014)

| NAMES Paracoccidioidomycosis, South American Blastomycosis |

| DISEASE Chronic pulmonary or disseminated disease is common (90% of cases) and may mimic malignancy or tuberculosis. The most common general signs and symptoms are weight loss, lymph node enlargement, mucous lesions, weakness, and fever. Cough, usually productive, and dyspnoea are commonly reported respiratory symptoms. Pulmonary tuberculosis co-exists in 10-20% of those with pulmonary involvement. Other sites affected include the adrenal glands, the CNS, the cervical and submandibular lymph nodes, the intestines, bones or joints, the epididymis, the liver and the spleen. The multifocal or disseminated may present with pain during mastication, excess saliva and odynophagia. A few cases have been reported in AIDS. |

| FUNGI Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii |

| GLOBAL BURDEN Endemic to all Latin America, especially Brazil. The larger number of cases has been reported in Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina, Uruguay, Ecuador, Colombia, Peru and Paraguay. Relatively few cases are reported from Bolivia or French Guiana. In Brazil probably ~ 3,500 annually, so <10,000 worldwide. The incidence may be declining because of changing agricultural practices and greater urbanization. |

| RISK FACTORS Males are affected much more frequently than females, although a similar sex frequency is seen in pre-pubertal girls and post-menopausal women. Oestrogen blocks the mould to yeast transition in the fungus, preventing infection. AIDS increases the risk of more severe infection. Smoking probably increases the risk of chronic pulmonary disease. |

| DIAGNOSIS Chest radiographs shown bilateral disease in >90% of cases, usually occupying over a 1/3 of the lung area. Nodular and combined nodular/fibrotic appearances are typical of the chronic form of paracoccidioidomycosis. Diffuse lung infiltrates are more typical of the acute form. The diagnosis is usually made by culture from sputum or biopsy although the histologic appearances of P. brasiliensis are highly characteristic. Routine fungal culture of all specimens submitted for TB culture, increases the yield in endemic areas. |

| TREATMENT Itraconazole is highly effective in non-immunocompromised patients. Amphotericin B is preferred in patients with severe pulmonary infection or in immunocompromised patients with disseminated disease. Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is an alternative for those with chronic forms of disease with an 80% efficacy. CURRENT GUIDELINES |

| OUTLOOK Overall estimated 5-30% mortality, sometimes as a result of co-morbidity such as tuberculosis or AIDS. Late diagnosis contributes to death. The main sequelae of paracoccidioidomycosis include worsening breathlessness due to pulmonary fibrosis and cavitation, adrenal gland dysfunction (~30%), dysphonia and/or laryngeal obstruction, reduced mouth opening and epilepsy and/or hydrocephalus (~15% ). |

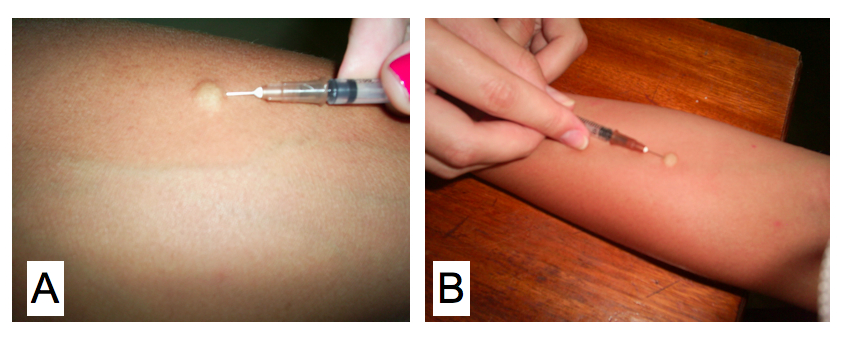

Cutaneous skin test for a delayed type hypersensitivity reaction using the antigen paracoccidioidin. Kindly supplied by Eduardo Bagagli and Marcello Franco

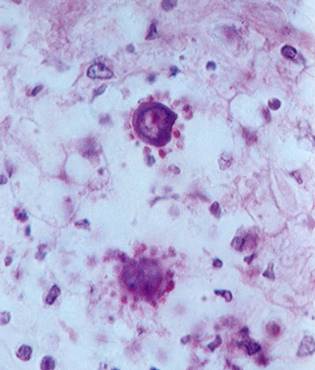

P. brasiliensis in tissue, showing the ‘ship’s wheel’ appearance, not seen in any other infection (kindly supplied by Prof Dr Luiz Cosme Cotta Malaquias)

Colony appearance of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis on mycobiotic agar at 26◦C for 20 days

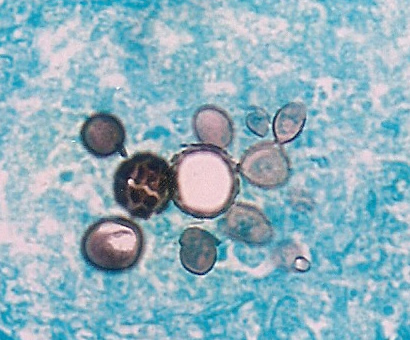

Microscopy of Paracoccidiodes. Kindly supplied by Eduardo Bagagli and Marcello Franco

Blastomycosis

| DISEASE After inhalation, primary pulmonary infection follows. Cutaneous and bone lesions indicate dissemination. Meningitis occurs in <5% of immunocompetent patients. Occasionally rapidly-progressive pneumonia leading to the adult respiratory distress syndrome is seen, which is more common in AIDS. The disease is usually relatively indolent but blastomycosis in AIDS and other immunocompromised patients has a more rapid course, and a much higher frequency of CNS involvement, usually as a brain abscess. |

| FUNGI Blastomyces dermatitidis |

| GLOBAL BURDEN Blastomycosis is endemic to North America and has been noted occasionally in Africa and India. Studies performed in the USA showed that the incidence of this infection is between 0.5-7 cases/100,000 people. Contact rates with the fungus are probably much higher. |

| RISK FACTORS Most affected patients were healthy adults, particularly middle aged men undertaking sports or work in rural or wild areas. Immunocompromised patients are at increased risk of severe disease. |

| DIAGNOSIS Culture of the organism from sputum or (skin) biopsy material. The histological appearance of B. dermatitidis is distinctive with yeasts cells with broad-based budding, unlike C. neoformans in which the budding is from a narrow base. An antigen test is available in one US laboratory. |

| TREATMENT Itraconazole is highly effective in non-immunocompromised patients. Bone and joint disease require 12 months of therapy. Amphotericin B is preferred in patients with severe pulmonary or brain infection, or immunocompromised patients with disseminated disease. CURRENT GUIDELINES |

| OUTLOOK In non-immunocompromised patients cure rates of 95% are typical. Outcomes are good even in very ill patients, if the diagnosis is made early and amphotericin B therapy initiated. For more information: Blastomycosis: A Review of Mycological and Clinical Aspects (Linder, Kauffman & Miceli, 2023). |

Skin lesions of blastomycosis occurring along a scar line (Koebner phenomonen)

Cutaneous blastomycosis on the nose of a woman (left) from the Midwest USA, who received itraconazole for 6 months and responded well (right)