A systematic review has identified fourteen cases of non-feline sporotrichosis linked with insect bites. Sporothrix schenckii was identified in six cases; the species was not determined in the remainder. The infection sites identified in some of the cases were the upper extremity (two cases), face (one case), lower extremity (2 cases), and left arm (one case). The transmission route was via insect bite or sting, but the mechanism is seemingly unclear; whether they inoculate the infectious agent or merely facilitate its entry through the bite or sting.

A significant finding in the analysis was that, across the non-feline vectors evaluated in the review, invertebrates were mostly involved in sporotrichosis among younger individuals compared with adults. However, given the sample size, there may be an interpretation bias to this observation. Overall, this review evidently attests that there may be more to sporotrichosis transmission, beyond the previously known routes, which are traumatic inoculation and feline transmission. Authors, however, stressed the fact that insect bites should not be classified as a zoonotic transmission, as they do not develop active sporotrichosis and are unlikely to serve as biological reservoirs.

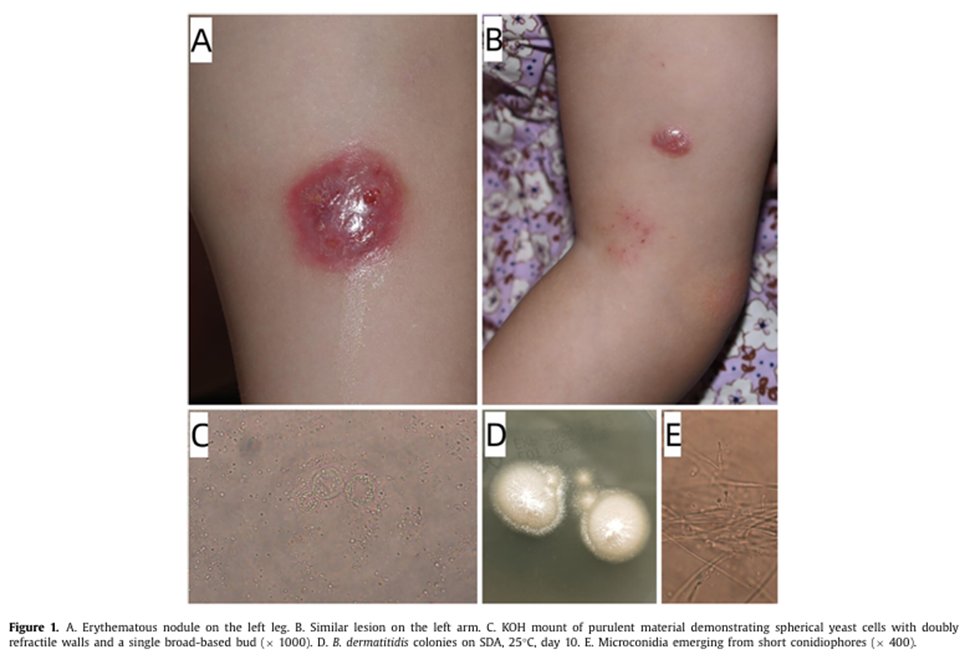

Besides being implicated in the transmission of sporotrichosis, insect bites have recently been associated with blastomycosis. Liu and colleagues reported a Chinese-Canadian girl initially diagnosed with insect bite dermatitis in Canada, which showed a poor response to treatment. Following a trip to China, a direct microscopic examination of the purulent material from the skin nodules showed spherical yeast cells with doubly refractile walls and single broad-based budding, which were suggestive of protothecosis or coccidioidomycosis but later identified by metagenomic next- generation sequencing (mNGS) as Blastomyces dermatitidis, and subsequently confirmed by fungal culture and ITS sequencing.

As previously described for sporotrichosis, other means of transmission may have also evolved in cases of blastomycosis. Although primarily acquired via the inhalation of airborne conidia, giving rise to the respiratory form of blastomycosis, the disease can also occur from a direct cutaneous inoculation of the pathogen, resulting in primary cutaneous blastomycosis. The latter is not commonly encountered but may explain the link between insect bites and blastomycosis.