In August 2017, hurricane Harvey devastated the Houston metropolitan area and adjacent counties. Much of the post-hurricane clean-up was carried out by members of the public, with little or no personal protective equipment. As the damage was mostly caused by flooding, the public were exposed to greater levels of mould, due to these damp conditions, and mould remediation was one of the prime concerns during the clean-up.

A new study carried out for the Center for Disease Control looks at the impact that this increased level of mould exposure had on immunocompromised area residents. One of the key findings was that an increased use of voriconazole and amphotericin B was seen at the cancer center, used as a test site, in the 12-month period following the hurricane. Patients that developed IMIs post-Harvey had significantly higher in-hospital mortality and tended to have higher ICU admission rates than patients with IMIs pre-Harvey.

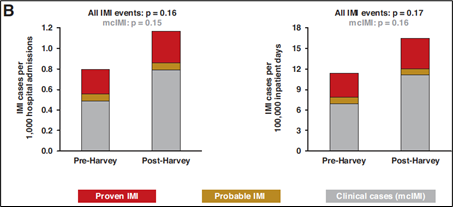

The authors also found that hurricane Harvey did not cause significant changes to proven or probable invasive mould infections, but almost doubled the recovery of moulds from respiratory cultures in patients living in Harvey-affected areas. This is likely to reflect increased airway colonization. This points to a need for long-term studies of environmental events, including looking at non-infectious mould-associated diseases and clinical management of IMIs after environmental events such as these. The EORTC/MSG criteria are not sufficiently sensitive for this type of epidemiological investigation for invasive mould infections.

You can read more about the study here.